‘’Like many businessmen of genius he learned that free competition was wasteful, monopoly efficient. And so he simply set about achieving that efficient monopoly.’’

Mario Puzo, The Godfather, Book III

Mafia families depicted in this 1969 Mario Puzo book and its 1972 Hollywood adaptation has had a profound impact in shaping the ideas of both the masses and the policy makers about organized crime, including the perception of its threats, its structure and mode of operations, and consequently influenced the legislative and law enforcement responses. The far-reaching effects this book and movie has had, among other things, attest to the fact that organized crime has not gotten the attention it deserved. It does not get it still even though its threats are too real and there is much to deliberate on, beginning from the difficulties in defining it to what should be the effective legislative and administrative responses.

Increasingly transnational organized crime has now emerged as one of the greatest threats to global security and human rights although its local variance has a long history and its international connections are also not altogether a new phenomenon. Defining organized crime, however, is a difficult task, because despite the attention from policy makers at every level, national and international, it is not a very well understood concept. Ideas about how it works and what constitutes organized crime suffer from lack of empirical data and as a result are passionately disputed amongst experts belonging to different schools of thought.

There are several theories ranging from the old and severely criticized alien-conspiracy theory and bureaucratic or illegal entrepreneurship models to the more contemporary protection theory, social embeddedness approach and the logistical and situational approach attempting to explain what it is and how it works. But two general notions can be discerned: the first is there are large and stable structured enterprises which carry on one or several criminal activities for profit. The Italian La Cosa Nostra, Japanese Yakuza, Chinese Triads etc. are well-known examples. The second notion conceptualizes organized crime as carrying out of a set of serious crimes for profit mainly in illegal goods and services, by largely loosely connected and diverse and flexible role players.[1] Large mafia-like organizations exist only in few countries where it emerged taking advantage of weak-state institutions; but criminal activities for profit are carried out everywhere, with its structural formation and operational strategies varying from one country to another.

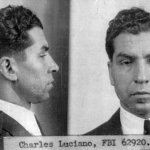

When the term first came into popular usage in the U.S., organized crime was synonymous with the Italian Mafia. This alien-conspiracy theory that Italian immigrants brought this problem with them and gained control over America’s underworld was the dominant policy position for decades (starting from the late 1940s, consolidating all through to the 80s) even though it was criticized heavily by academics for being at odds with empirical facts. The U.S. however developed approaches, in both law and practice, and was determined in exporting its ideas abroad. The use of wire-tapping and other forms of electronic surveillance has been its principal strategy.

The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 put electronic surveillance under a regulatory regime, but it was deemed insufficient in its scope and the Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act of 1970 provided a much stronger antidote to organized crime with longer sentences, more invasive investigative methods and even provided victims options to bring Civil Actions to recover losses. RICO has been championed as the greatest policy response to organized crime and has been aggressively promoted to other countries as a model by the U.S.[2] Authors have showed how the U.S. exerted direct influence in pressuring foreign states to harmonize their laws in its reflection and there is evidence of this influence succeeding in a host of countries not only in North America, but all across Europe and other places. The United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime, 2000 (UNCATOC) was in many ways a push to make these concerns and accepted best practices, which is really U.S. practices, to create a guiding International regulatory regime to pressure countries into adopting harmonized laws.[3]

UNCATOC is the first global agreement to comprehensively tackle organized crime. The convention was adopted by the UN General Assembly on November 15, 2000 and entered into force on September 29, 2003. The extremely broad definition of transnational organized crime provided here owed a part to the European Union’s Joint Directive of 1998, which was the EU guiding principles on organized crime until replaced by the Framework Decision of 2008, which retained the its duel-model (a compromise between Common Law and Civil Law traditions) character. Bangladesh acceded to the Convention in 2011 with one reservation (Paragraph 2 of Article 35, relating to the Settlement of Disputes between States).

Organized crime-specific legislation all over the world has taken on the notion of a structured criminal entity as its guiding light, even though it can be interpreted to include other loosely connected or irregularly structured forms of criminal enterprises, owing both to the influence of the U.S. model and the experiences of the home jurisdiction. For example, in India the State of Maharashtra has a guiding legislation: Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999. Maharashtra had notoriously been the home of Dawood Ibrahim of the D-Company and has a long history of protection, extortion, and resulting violence including high profile murders in the film industry. In Australia, the laws developed around the concerns for the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs. Australia adopted federal legislations in 2010[4] and almost every State passed its own legislation, even though some of them were reluctant for a period.

Bangladesh has had troubles with large urban criminal groups like the notorious 7-star and 5-star groups based in Dhaka and lead by Sweden Aslam, Kala Jahangir, Subrata Bain and others, the alleged dons of the underworld, referred to as top terrors or terrorists (Sheersho Shontrashi). A large number of crimes in the country including dacoity, robbery, extortion, kidnapping for ransom, piracy in the forests, rivers and sea, grabbing lands illegally including island chars (Char Dakhal), among many others with a long history and also the relatively new ones ranging from bank robberies, heists or thefts, to what is now popularly referred to as the ‘Oggan Party Crime’, are all forms of organized criminal activities, the modus operandi and structural formations varying considerably across this wide assortment.

Bangladesh does not have any special law dedicated solely to organized crimes, but has Acts responding to specific areas like drugs control, human trafficking etc. Certain crimes are regulated by a large number of Acts like currency smuggling which attracts provisions from the Special Powers Act, Customs Act, Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, Import and Export Control Act etc. Other offences are tried under the Penal Code, 1860, which is a dated law in numerous respects[5]and is extremely underequipped to handle organized crime, to be able to bring every role-players involved under the book. The Money Laundering Prevention Act, 2012 goes some way in addressing this issue by including organized crime and racketeering in its list of predicate offences but any such list can hardly be expected to be exhaustive and the procedural aspects are narrow and necessarily focus on financial transactions. It cannot be expected to criminalize participation in an organized criminal group, for instance.

It can be argued that an organized crime legislation can address both dominant notions through a comprehensive definition and an effective punitive and corrective regime. It can bring every role player involved in a specific organized crime, belonging both to the underworld and licit factions of the society including corrupt law enforcement and other government officials and lawyers, without whom organized crime groups cannot function or sustain. It should also prescribe enhanced but logical punishments, while providing detailed checks and balances to ensure human rights of one and all are protected in the process. The Law Commission may bring experts from the various law enforcement agencies (the Organized Crime Department of the CID is a prime example), academics and practitioners specializing in areas as diverse as human rights, criminology, criminal law, organized crime, money laundering and terrorism, and policy makers and other relevant stake holders to draft the law, which may very well have far reaching international impact, as the global order suffers at present from the ambiguity in its understanding of organized crime and hesitancy about effective response mechanisms. It can even inspire the policy makers and lead them to think in a wider context and move towards an improved and progressive criminal justice administration altogether with the overhaul of the Penal Code and related enforcement mechanisms.

[1]Letizia Paoli and Tom Vander Beken, ‘Organized Crime: A Contested Concept’ in Letizia Paoli (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Organized Crime (OUP 2014)

[2] Margaret Beare and Michael Woodiwiss, ‘U.S. Organized Crime Control Policies Exported’ in Letizia Paoli (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Organized Crime (OUP 2014)

[3]See for example: Ethan Nadelmann, Cops across Borders: The Internationalization of U.S. Criminal Law

Enforcement (Pennsylvania State University Press 1993) and Michael Woodiwiss, Organized Crime and American Power: A History (University of Toronto Press 2003)

[4] Crimes Legislation Amendment (Serious and Organised Crime) Act, 2010 and the Crimes Legislation Amendment (Serious and Organised Crime) Act (No. 2) 2010.

[5]Drafted by the British, who don’t have a codified penal statute themselves, necessarily in furtherance of the then crown’s imperial interests and modeled on Napoleon’s Penal Code of 1812, which France replaced herself by the Penal Code of 1994

People reacted to this story.

Show comments Hide commentsClearly written and thought-provoking article !! You deserve a hug, buddy 🙂